browsers overview

moteurs de rendus

cf The third browser war is over and it's a bloodshed - Daniel Glazman - WEB2DAY 2016

| - | modern | standards | cross platform | speed | author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gecko | OK | OK | OK | OK | Mozilla Foundation |

| WebKit | OK | OK | OK | OK | Apple |

| Blink | OK | OK | OK | OK | chromium (Google) |

| Edge | OK | OK | KO | OK | EdgeHTML (Microsoft) |

| Servo | OK | OK | OK | OK | servo.org (Mozilla Foundation) |

Trident moteur de IE4 à IE11) : stoppé.

Servo écrit en Rust est le petit nouveau. MultiThreadé et layout parallèle. Ultra performant. Va probablement beaucoup changer la donne sur mobile. Meilleure vitesse mais surtout meilleure conso. (d'où la collaboration Mozilla / Samsung).

Opera a abandonné Presto et est passé sur Blink

Un process par tab, chaque process multithreadé + layout parallèle = gains x30 à x50.

C'est officiel, Microsoft Edge sera désormais basé sur Chromium (src)

Cela signifie que Microsoft va remplacer son moteur de rendu EdgeHTML et son moteur JavaScript Chackra par Blink et V8 de Chromium.

Microsoft prévoit encore de publier le nouveau Microsoft Edge sur toutes les versions prises en charge de Windows (c'est-à-dire Windows 7 et Windows 8), mais sans se limiter à son OS.

Le passage à Chromium prendra environ un an, selon Microsoft, et une préversion sera prête début 2019.

browsers bug trackers

The browser's main functionality

The main function of a browser is to present the web resource you choose, by requesting it from the server and displaying it in the browser window. The resource is usually an HTML document, but may also be a PDF, image, or some other type of content. The location of the resource is specified by the user using a URI (Uniform Resource Identifier).

The way the browser interprets and displays HTML files is specified in the HTML and CSS specifications. These specifications are maintained by the W3C (World Wide Web Consortium) organization, which is the standards organization for the web. For years browsers conformed to only a part of the specifications and developed their own extensions. That caused serious compatibility issues for web authors. Today most of the browsers more or less conform to the specifications.

Browser user interfaces have a lot in common with each other. Among the common user interface elements are:

- Address bar for inserting a URI

- Back and forward buttons

- Bookmarking options

- Refresh and stop buttons for refreshing or stopping the loading of current documents

- Home button that takes you to your home page

The browser's high level structure

- The user interface: this includes the address bar, back/forward button, bookmarking menu, etc. Every part of the browser display except the window where you see the requested page.

- The browser engine: marshals actions between the UI and the rendering engine.

- The rendering engine : responsible for displaying requested content. For example if the requested content is HTML, the rendering engine parses HTML and CSS, and displays the parsed content on the screen.

- Networking: for network calls such as HTTP requests, using different implementations for different platform behind a platform-independent interface.

- UI backend: used for drawing basic widgets like combo boxes and windows. This backend exposes a generic interface that is not platform specific. Underneath it uses operating system user interface methods.

- JavaScript interpreter. Used to parse and execute JavaScript code.

- Data storage. This is a persistence layer. The browser may need to save all sorts of data locally, such as cookies. Browsers also support storage mechanisms such as localStorage, IndexedDB, WebSQL and FileSystem.

How do browsers render a web page

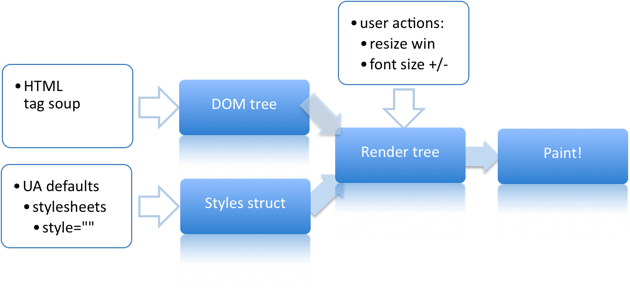

- The DOM (Document Object Model) is formed from the HTML that is received from a server.

- Styles are loaded and parsed, forming the CSSOM (CSS Object Model).

- On top of DOM and CSSOM, a rendering tree is created, which is a set of objects to be rendered (Webkit calls each of those a "renderer" or "render object", while in Gecko it's a "frame"). Render tree reflects the DOM structure except for invisible elements (like the tag or elements that have display:none; set). Each text string is represented in the rendering tree as a separate renderer. Each of the rendering objects contains its corresponding DOM object (or a text block) plus the calculated styles. In other words, the render tree describes the visual representation of a DOM.

- For each render tree element, its coordinates are calculated, which is called "layout". Browsers use a flow method which only required one pass to layout all the elements (tables require more than one pass).

- Finally, this gets actually displayed in a browser window, a process called "painting".

When users interact with a page, or scripts modify it, some of the aforementioned operations have to be repeated, as the underlying page structure changes.

HTML Parsing

HTML cannot be parsed using the regular top down or bottom up parsers. The reasons are:

- The forgiving nature of the language: the fact that browsers have traditional error tolerance to support well known cases of invalid HTML.

- The parsing process is reentrant. For other languages, the source doesn't change during parsing, but in HTML, dynamic code (such as script elements containing document.write() calls) can add extra tokens, so the parsing process actually modifies the input.

- Speculative parsing: for scripts, css, images we will forward.

The algorithm consists of two stages: tokenization and tree construction. Tokenization is the lexical analysis, parsing the input into tokens. Among HTML tokens are start tags, end tags, attribute names and attribute values. The tokenizer recognizes the token, gives it to the tree constructor, and consumes the next character for recognizing the next token, and so on until the end of the input.

CSS Parsing

It just creates the CSSOM.

Render / Frame Tree

While the DOM tree is being constructed, the browser constructs another tree, the render tree. This tree is of visual elements in the order in which they will be displayed. It is the visual representation of the document. The purpose of this tree is to enable painting the contents in their correct order.

Firefox calls the elements in the render tree "frames". WebKit uses the term renderer or render object. A renderer knows how to lay out and paint itself and its children. WebKit's RenderObject class, the base class of the renderers, has the following definition:

class RenderObject{

virtual void layout();

virtual void paint(PaintInfo);

virtual void rect repaintRect();

Node* node; //the DOM node

RenderStyle* style; // the computed style

RenderLayer* containgLayer; //the containing z-index layer

}

Each renderer represents a rectangular area usually corresponding to a node's CSS box, as described by the CSS2 spec. It includes geometric information like width, height and position. The box type is affected by the "display" value of the style attribute that is relevant to the node (see the style computation section). Here is WebKit code for deciding what type of renderer should be created for a DOM node, according to the display attribute:

RenderObject* RenderObject::createObject(Node* node, RenderStyle* style)

{

Document* doc = node->document();

RenderArena* arena = doc->renderArena();

...

RenderObject* o = 0;

switch (style->display()) {

case NONE:

break;

case INLINE:

o = new (arena) RenderInline(node);

break;

case BLOCK:

o = new (arena) RenderBlock(node);

break;

case INLINE_BLOCK:

o = new (arena) RenderBlock(node);

break;

case LIST_ITEM:

o = new (arena) RenderListItem(node);

break;

...

}

return o;

}

Layout

When the renderer is created and added to the tree, it does not have a position and size. Calculating these values is called layout or reflow.

HTML uses a flow based layout model, meaning that most of the time it is possible to compute the geometry in a single pass. Elements later in the flow'' typically do not affect the geometry of elements that are earlierin the flow'', so layout can proceed left-to-right, top-to-bottom through the document. There are exceptions: for example, HTML tables may require more than one pass.

The coordinate system is relative to the root frame. Top and left coordinates are used.

Layout is a recursive process. It begins at the root renderer, which corresponds to the element of the HTML document. Layout continues recursively through some or all of the frame hierarchy, computing geometric information for each renderer that requires it.

The position of the root renderer is 0,0 and its dimensions are the viewport–the visible part of the browser window. All renderers have a "layout" or "reflow" method, each renderer invokes the layout method of its children that need layout.

Dirty bit system

In order not to do a full layout for every small change, browsers use a "dirty bit" system. A renderer that is changed or added marks itself and its children as "dirty": needing layout.

There are two flags: "dirty", and "children are dirty" which means that although the renderer itself may be OK, it has at least one child that needs a layout.

The layout algorithm

- Parent renderer determines its own width.

- Parent goes over children and:

- Place the child renderer (sets its x and y).

- Calls child layout if needed–they are dirty or we are in a global layout, or for some other reason–which calculates the child's height.

- Parent uses children's accumulative heights and the heights of margins and padding to set its own height–this will be used by the parent renderer's parent.

- Sets its dirty bit to false.

Paint

In the painting stage, the render tree is traversed and the renderer's "paint()" method is called to display content on the screen. Painting uses the UI infrastructure component.

Repaint

When changing element styles which don't affect the element's position on a page (such as background-color, border-color, visibility), the browser just repaints the element again with the new styles applied (that means a "repaint" or "restyle" is happening).

Reflow

When the changes affect document contents or structure, or element position, a reflow (or relayout) happens. These changes are usually triggered by:

- DOM manipulation (element addition, deletion, altering, or changing element order);

- Contents changes, including text changes in form fields;

- Calculation or altering of CSS properties;

- Adding or removing style sheets;

- Changing the "class" attribute;

- Browser window manipulation (resizing, scrolling);

- Pseudo-class activation (:hover).

How browsers optimize rendering

Browsers are doing their best to restrict repaint/reflow to the area that covers the changed elements only. For example, a size change in an absolute/fixed positioned element only affects the element itself and its descendants, whereas a similar change in a statically positioned element triggers reflow for all the subsequent elements.

Another optimization technique is that while running pieces of JavaScript code, browsers cache the changes, and apply them in a single pass after the code was run. For example, this piece of code will only trigger one reflow and repaint:

// only 1 reflow and repaint will actually happen

var $body = $('body');

$body.css('padding', '1px'); // reflow, repaint

$body.css('color', 'red'); // repaint

$body.css('margin', '2px'); // reflow, repaint

However, as mentioned above, accessing an element property triggers a forced reflow. This will happen if we add an extra line that reads an element property to the previous block:

var $body = $('body');

$body.css('padding', '1px');

$body.css('padding'); // reading a property, a forced reflow

$body.css('color', 'red');

$body.css('margin', '2px');

As a result, we get 2 reflows instead of one. Because of this, you should group reading element properties together to optimize performance (see a more detailed example on JSBin).

There are situations when you have to trigger a forced reflow. Example: we have to apply the same property ("margin-left" for example) to the same element twice. Initially, it should be set to 100px without animation, and then it has to be animated with transition to a value of 50px. You can study this example on JSBin right now, but I'll describe it here in more detail.

We start by creating a CSS class with a transition:

.has-transition {

-webkit-transition: margin-left 1s ease-out;

-moz-transition: margin-left 1s ease-out;

-o-transition: margin-left 1s ease-out;

transition: margin-left 1s ease-out;

}

Then proceed with the implementation:

// our element that has a "has-transition" class by default

var $targetElem = $('#targetElemId');

// remove the transition class

$targetElem.removeClass('has-transition');

// change the property expecting the transition to be off, as the class is not there

// anymore

$targetElem.css('margin-left', 100);

// put the transition class back

$targetElem.addClass('has-transition');

// change the property

$targetElem.css('margin-left', 50);

This implementation, however, does not work as expected. The changes are cached and applied only at the end of the code block. What we need is a forced reflow, which we can achieve by making the following changes:

// remove the transition class

$(this).removeClass('has-transition');

// change the property

$(this).css('margin-left', 100);

// trigger a forced reflow, so that changes in a class/property get applied immediately

$(this)[0].offsetHeight; // an example, other properties would work, too

// put the transition class back

$(this).addClass('has-transition');

// change the property

$(this).css('margin-left', 50);

Now this works as expected.

Practical advice on optimization

Summarizing the available information, I could recommend the following:

- Create valid HTML and CSS

- Do not forget to specify the document encoding

- Styles should be included into

- Scripts appended to the end of the tag. Think about async and defer attribute.

- Try to simplify and optimize CSS selectors (this optimization is almost universally ignored by developers who mostly use CSS preprocessors). Keep nesting levels at a minimum. This is how CSS selectors rank according to their performance (starting from the fastest ones):

- Identificator: #id

- Class: .class

- Tag: div

- Adjacent sibling selector: a + i

- Parent selector: ul > li

- Universal selector: *

- Attribute selector: input[type="text"]

- Pseudoclasses and pseudoelements: a:hover You should remember that browsers process selectors from right to left, that's why the rightmost selector should be the fastest one — either #id or .class:

- div * {...} // bad

- .list li {...} // bad

- .list-item {...} // good

list .list-item {...} // good

- In your scripts, minimize DOM manipulation whenever possible. Cache everything, including properties and objects (if they are to be reused). It's better to work with an "offline" element when performing complicated manipulations (an "offline" element is one that is disconnected from DOM and only stored in memory), and append it to DOM afterwards.

- To change element's styles, modifying the "class" attribute is one of the most performant ways. The deeper in the DOM tree you perform this change, the better (also because this helps decouple logic from presentation).

- Animate only absolute/fixed positioned elements if you can.

- It is a good idea to disable complicated :hover animations while scrolling (e.g. by adding an extra "no-hover" class to ).